Teaching

Before traveling to Rwanda, students explore the case of Rwanda within a broader theoretical context. They discover the analytical and definitional challenges of classifying an episode of mass violence as genocide; explore the conditions under which the genocide occurred; examine how and why civilians were mobilized into killing militias; and finally, consider how the genocide shaped justice, reconciliation, and memory construction processes in Rwanda.

This first week enables students to develop a theoretical and empirical understanding of the causes, course, and consequences of the genocide in Rwanda. This prepares students for two weeks in Rwanda, during which they visit sites of memory and discover how Rwandans tell their own difficult history. Thus, throughout the course, students are encouraged to compare Western and local forms of knowledge. After visiting numerous memorial sites, students begin to examine the judicial responses to genocide. They meet with a gacaca judge who explains the history of gacaca and the structural and personal challenges she encountered in her work. Next, students visit a reconciliation village, where they meet with genocide survivors and individuals who participated in the genocide. They hear from the community, learning about their personal experiences and asking questions about reconciliation efforts. Students also meet with numerous experts (government and NGOs) whose work aims to preserve the memory of the 1994 genocide and prevent future genocides. This experiential learning fosters fruitful discussions regarding effective strategies for pursuing justice and reconciliation after genocide and the construction of collective memory

Genocide, Justice, and Memory

(Study Abroad Course)

Transitional Justice Mechanisms

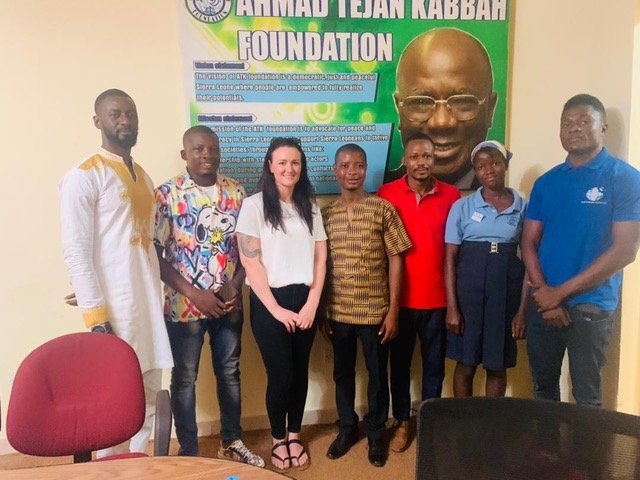

(University of Sierra Leone)

In this course, students examine how nations have historically responded to episodes of mass violence. Students explore the social repercussions and political consequences of large-scale political violence, such as genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. Together, we ask: How do successor regimes balance the demands for justice with the need for peace and reconciliation? And how is the public memory of atrocities constructed? We began by defining various forms of mass violence, laying the theoretical groundwork underpinning transitional justice, and understanding collective memory (and forgetting). We next explore truth commissions, criminal courts, and reparative and local forms of justice, drawing upon case studies from sub-Saharan Africa and worldwide. Finally, we examine how the public memory of atrocities is constructed, focusing on the impact of transitional justice mechanisms on education. This involves visiting the local peace museum and the UN Special Court for Sierra Leone.

This course is motivated by two questions: why are some kinds of killing criminalized and others sanctioned, and why do people kill? During this course, students grapple with these questions. We begin by defining and theorizing what killing (and more broadly violence) are, how crime is socially constructed, and the process in which different types of killing have become criminalized throughout history. We end the course by examining why individuals kill and considering whether the motivations of those who kill differ with the type of killing. Consulting both historical and contemporary cases of killing, students examine the various aspects of killing including: criminalization, motivations, the social construction of victims and perpetrators, and more.

Sociology of Killing